COP21 chose aspirational targets, rather than binding targets. It was a good outcome for the Paris Climate Conference.

An attempt to implement binding emission reduction targets at the Paris Climate Conference, COP21, would not have achieved as much. Under that scenario, only leaders who were being pushed by an ideological agenda would have made substantial commitments. As it turned out, only China held back from making a reasonable commitment, while actually working behind the scenes to take more drastic action (or at least that is what we currently think).

COP21 – not the IPCC

The IPCC has been ideologically blinded by its 1990 ambition to model the climate out to the future. This has proven to be “too difficult.” In response the “true believers” in this strategy have committed themselves to outrageous advocacy of a “climate disaster” position.

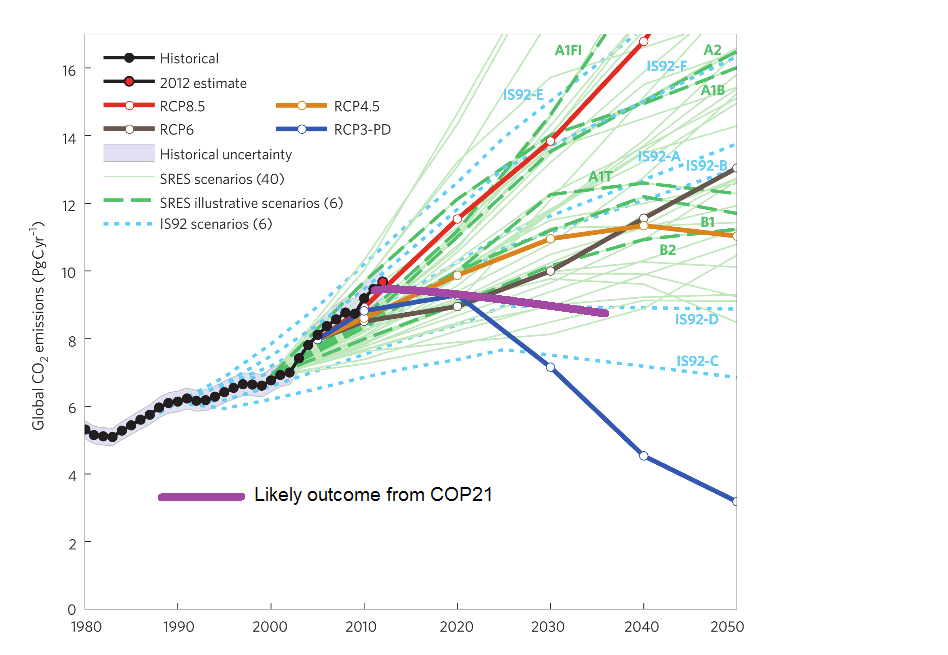

This is well illustrated in an article by Glen P. Peters, Robbie M. Andrew, Tom Boden, Josep G. Canadell, Philippe Ciais, Corinne Le Quéré, Gregg Marland, Michael R. Raupach and Charlie Wilson, “The challenge to keep global warming below 2?°C,” NATURE CLIMATE CHANGE | VOL 3 | JANUARY 2013. In this article, it was claimed that the world was on a trajectory of totally out-of-control climate change (represented on the chart below as RCP 8.5).

The authors constructed a chart to demonstrate their point, and made a prediction of 2012 CO2 emissions that was more like a guess that supported their proposition. The Australian CSIRO even cited this article to me in 2015, even though evidence from 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 CO2 atmospheric levels showed that emissions were likely to have fallen below the estimates in this graph.

It is now clear that Peters, et al. were wrong. Despite this, the orthodox position is that the collective known as the IPCC can do no wrong. Yet the politicians at COP21 do not appear to have believed them. They came up with plan that would actually work, which was not based on a “climate disaster” scenario, such as presented by Peters, et al.

We can compare the outrageous predictions of IPCC-linked climate scientists with the actual likely outcome, at least as indicated by hard evidence of the actual known CO2 atmospheric levels up to the end of 2015.

A caveat has to be raised for 2016, since the atmospheric levels of CO2 have risen much more than expected. Most of this increase can be attributed to the El-Nino effect, with a higher temperature resulting in more CO2 being released from the ocean. However, this does not entirely explain the increase, and we have to wait until June 2017, when the El-Nino effect has been fully purged from the data to be really sure about this. (Earlier I had written that the extra atmospheric CO2 was possibly due to emissions from the Middle-East war. While the war did increase atmospheric CO2, I am willing to concede that it is both temporary and was dwarfed by the El-Nino effect. I have now a more robust explanation, but publication of that explanation, even in this form, will have to wait until after June.)

CO2

A close to ideal strategy would be something like a 2% reduction in CO2 emissions per year per nation for the next 10 years from a 2013 base. COP21 did not adopt this target, but it headed in this direction.

Such a target is only fairly applied to those nations above the world average per person of CO2 emissions of around 5 tonnes per person. Using 2010 data, the following are the most important countries in regard to CO2 emissions:

China – 8 billion tonnes per year – 6 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

USA – 5 billion tonnes per year – 17 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

India – 2 billion tonnes per year – 1.6 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Russia – 2 billion tonnes per year – 12 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Japan – 1 billion tonnes per year – 9 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Germany – 750 million tonnes per year – 9 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Iran – 570 million tonnes per year – 7 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

South Korea – 560 million tonnes per year – 11 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Canada – 500 million tonnes per year – 13 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

UK – 500 million tonnes per year – 8 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Saudi Arabia – 460 million tonnes per year – 16 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

South Africa – 460 million tonnes per year – 9 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Mexico – 440 million tonnes per year – 4 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Indonesia – 430 million tonnes per year – 2 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Brazil – 420 million tonnes per year – 2 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Italy – 410 million tonnes per year – 7 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Australia – 370 million tonnes per year – 16 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

France – 360 million tonnes per year – 5.5 tonnes per person – down to 5 tonnes

Poland – 320 million tonnes per year – 8 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Ukraine – 300 million tonnes per year – 7 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Turkey – 300 million tonnes per year – 4 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Thailand – 300 million tonnes per year – 4.5 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Spain – 300 million tonnes per year – 5.5 tonnes per person – down to 5 tonnes

Kazakhstan – 250 million tonnes per year – 14 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Malaysia – 220 million tonnes per year – 7 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Egypt – 200 million tonnes per year – 2.5 tonnes per person – no reduction target

Venezuela – 200 million tonnes per year – 7 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Netherlands – 180 million tonnes per year – 11 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Argentina – 180 million tonnes per year – 4 tonnes per person – no reduction target

UAE – 170 million tonnes per year – 18 tonnes per person – 2% target applies

Taiwan should also be included, but is not listed in the UN data.

Methane

It is interesting that Methane is not the problem that IPCC predicted it would be. However, holding Methane emissions levels constant could be a good aspirational target.

Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous Oxide, particularly from transportation, is not open to easy attack. A solution to the growth in nitrous oxide emissions will probably depend upon the development of electric cars as a viable alternative to petrol and diesel vehicles. That is likely to be 10 years away. The target here could be to develop alternatives to current vehicle engines in that period.

HCFCs

Similarly, while atmospheric levels of CFCs are declining, atmospheric levels of HCFCs are growing. The target here could be to develop alternatives to HCFCs over the next 10 years.

History of this discussion

An earlier version of this article was published before COP21. It can found here.

Useful information. Lucky me I found your website

accidentally, and I’m surprised why this twist of fate did not took place in advance!

I bookmarked it.