While the national leaders at the APEC 2016 conference in Peru are willing to acknowledge that “some people have been left behind,” there is little agreement on the action required to fix this.

Peru points the way

In an interview translated on SBS TV (in Australia), Peru’s Finance Minister, Mercedes Araoz said, “What they [the discontented voters] are taking issue with is valid in all societies in the face of globalisation, and perhaps a bit of rejection of it. The request is to apply some mechanism to make it more inclusive.”

Nowhere is the need more obvious to make national economies stronger & fairer than in the developing world. Apart from their own entrenched income inequalities, they are also faced with a most daunting prospect: the first-mover-advantage over them of developed nations. Indeed, it was the intention of the TPP to entrench that advantage well into the foreseeable future. For the sake of Peru, and other vulnerable nations, it is fortunate that this treaty has been put on hold. May it be buried forever, and along with it an attempt to game the system in favor of the largest corporations in the world.

Ms Araoz’s plea

Responding to Ms Araoz’s plea, I argue that the required first step is to convince national governments that they can manage their own affairs. Once that concept begins to be reconsidered, then each national government can look at the way in which it can increase the prosperity of its people.

We can look at the USA as an example. Prior to the current obsession with globalization, which started about 30 years ago, the USA domestic sales of goods and service was about 94% of GDP. They made stuff and consumed it themselves. It was a happy and prosperous period, when people served each other and shared a national vision. Now domestic sales are about 84% of GDP, and there is considerable angst throughout large sections of the nation.

Higher exports and imports in the USA have had three results:

- Many goods are much cheaper now than before, thus making the consumer (who has a job) better off.

- Businesses are more able to compete in the export market because they have access to cheaper labor, such as from Mexico.

- Whole cities have been devastated by loss of entire industries, and in many once large and prosperous regions of America the people are desperately looking just to survive. The cheap goods are not much use to them.

So one could ask, “Has the move towards free trade been worth the cost?” The answer has to be both yes and no, depending upon who you ask. Winners have won even more, losers have lost most of what they had before.

A new Economic Mechanism from APEC 2016

When it comes to finding a new economic mechanism at APEC 2016, one doesn’t need to be too concerned about developed nations. They have mature democracies, and the voice of the people will guide their leaders to work through the issues that I have discussed. The role of the leaders of APEC 2016 should be to find a new mechanism that will be useful for developing and emerging nations.

Thinking people must know that, while developing nations have improved their national GDP by exporting to the developed world, this is not a very good long-term strategy. If developing nations look forward to a future as just being a source of cheap imports for the West they are condemning themselves to a future of relative poverty. While there is any nation in the world that doesn’t take control of its own destiny, there will always be a cheaper source of labor upon which the West can depend.

Ms Araoz’s plea at APEC 2016 implies the need to create a mechanism that will enable each developing nation to develop a diverse economy, in which all its people can prosper. Such a mechanism would enable the full talents of its own people to be exercised within that nation, with the more skilled and talented being able to raise the (economic) boat for the entire nation.

Yet the question is, “How can this be done when the West owns almost all of the intellectual property, both that which is patented, and that which is inbuilt into their entire economic, government and educational system?”

A 20% Tariff would Level the Playing Field

The APEC and WTO objective of lowering all tariffs to zero rating is entirely misconceived. Such a strategy will not “lift all boats.” Rather, it will trap developing nations in a permanent dependency on the West. If APEC 2016 doesn’t change direction, the meeting can be considered to be a failure.

One of the strategies that could be adopted by APEC 2016 is to support the introduction of an extra 20% tariff across the board. This would give emerging industries in developing countries a chance to find a modest level of support so that they can find their feet. It never needs to be reduced below 20%, unless there really is a compelling case for goods to be 20% cheaper. What would be argument for that? The wealthy getting luxury goods cheaper?

A Hypothetical Example

Let us assume that there is a country with a population of 10 million people. In this country, the top 10% of the population earn 90% of the nation’s income. Most of the rest are either subsistence farmers or poorly paid factory workers. Let us assume that the national GDP is $40 billion, with the top 10% earning $36,000 each per year and the rest earning $450 each per year. In this country 40% of the national income is from exports, and it spends this on imports.

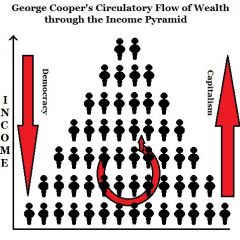

Now let us assume that a 20% tariff is applied across the board in addition to any current tariff. After this, innovative entrepreneurs are likely to see the opportunity to make many of the goods consumed by the top 10%, which were previously imported. As a result, demand for labor increases and whole new class of more highly skilled workers develops. As a result, a number of those previously in the bottom 90% now find themselves in a new echelon of society. Now the society’s division is 20% who command 80% of the nation’s GDP. While some of the relatively very rich will have lost some of their income along the way, following the disruption brought about by this reform, let us say that the nation’s GDP has now grown to $50 billion. All of this extra goes to the new top 20% of the population, so that their average income is now $23,000. This is lower than the previous average of $36,000, but it is spread over more people. The nation is already better off, but nothing has been done from the remaining 80% of the population.

Because there are now more relatively wealthy people, the service sector in the nation can grow as well, thus pushing up both wages and paid activity. The extra $10 million is now spent in the service sector, increasing the nation’s GDP to $60 billion. Most of this will go to the 80% poorer part of the population. This sector previously earned $450 per year; now these 8 million people share in the extra $10 billion, pushing up their average income by $1,250 per year.

Any reasonable and competent government would work towards ensuring that this virtuous circle continues to lift the income of these lower paid workers, through education, and improved skills at work.

Conclusion

It is cringe-worthy of the Australian Prime Minister, Malcolm Turnbull, to cite 1930s protectionism as if it provides the evidence for embracing free trade. Doesn’t he know that the 1930s were a very difficult period because of the crash of the world economies from over-active speculative activites in the 1920s?

Doesn’t Malcolm Turnbull know that America’s economic powerhouse was built in the 19th century, building its strength behind tariff walls?

Even less excusable, doesn’t Malcolm Turnbull know that the world became a much more prosperous place at the same time as protectionist regimes were in place in most of the nations of the world, namely, in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s?

Rather than protectionism being ridiculous, as Obama and Turnbull seem to think, the arguments presented here are just standard economics. Unfortunately, free trade advocates, many of whom are gathered at APEC 2016 seem to have stopped thinking from first principles, and have adopted a convenient, if bogus, theory.

A “protectionist scenario” has been replayed in every developed nation: it is now being played out in China. Why shouldn’t the rest of the developing world be encouraged to follow the same pattern?