Argentina’s economic malaise is almost entirely due to blindly accepting prepared economic prescriptions, rather than finding its own way forward. It started with socialism and then accepting Ricardo’s theory about Comparative Advantage, leading to the collapse of a once thriving economy.

Argentina is in the unique position as a country that had achieved advanced development in the early 20th century but experienced a reversal. This has inspired an enormous wealth of literature and diverse analysis on the causes of this decline, but there is little evidence that this analysis has come close to discovering the reason for Argentina’s economic malaise.

Argentina’s Economic Malaise & comparative advantage

The history of Argentina’s economic health is littered with pointers to the unhealthy consequences of the “advice” of economists.

Economic historians point out the Argentina’s economic advantages, placing it squarely in the real of Ricardo’s “comparative advantage.” Here is a summary presented in Wikipedia:

Argentina possesses definite comparative advantages in agriculture, as the country is endowed with a vast amount of highly fertile land. Between 1860 and 1930, exploitation of the rich land of the pampas strongly pushed economic growth. During the first three decades of the 20th century, Argentina outgrew Canada and Australia in population, total income, and per capita income. By 1913, Argentina was the world’s 10th wealthiest state per capita.

Ignoring the economists’ mantra that each country should concentrate of its own comparative advantage, from 1930 to 1976, the various governments of successfully diversified the nation’s economy by engaging in a process of industrialization, behind a protective tariff regime.

To the amazement of economists and economic historians, “Despite this [Argentina’s protectionist regime], up until 1962 the Argentine per capita GDP was higher than of Austria, Italy, Japan and of its former colonial master, Spain.” So one economic historian amazingly concluded, “Beginning in the 1930s, however, the Argentine economy deteriorated notably.”

So one can see, even though economic policies that do not respect Ricardo’s theory can serve a country very well, most economists are so blind they cannot see what stares them in the face.

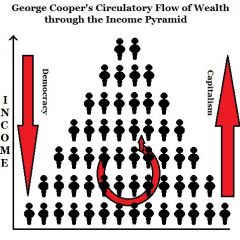

What they cannot or will not see is that no country is better off in the long term by concentrating only on their strengths. Only a diverse economy can work for everyone, not just those who are occupied in the “advantaged field.”

Argentina’s Economic Malaise – Peronism

Part of coup that seized power in 1943, Juan Perón became Minister of Labour. Campaigning among workers with promises of land, higher wages, and social security, he won a decisive victory in the 1946 presidential elections. Under Perón, the number of unionized workers expanded as he helped to establish the powerful General Confederation of Labor. This sowed the seeds for the later humiliation of Argentina’s economy.

Beginning in 1947, Perón took a leftward shift in economic policy, first breaking up with the “Catholic nationalism” movement. This led to gradual state control of the economy, reflected in the increase in state-owned property, control of rents and prices. The expansive macroeconomic policy, which aimed at the redistribution of wealth and the increase of spending to finance populist policies, led to inflation.[95]

Thus it is with socialism everywhere! The Whitlam experiment is Australia’s practical demonstration, with unsustainable higher wages, out of control inflation, and leading (socialist) economists saying, “There is nothing to see here – all is OK.”

In the 1950s and part of the 1960s, the country had a slow rate of growth in line with most Latin American countries. Stagnation prevailed during this period, and the economy often found itself contracting, mostly the result of union strife.[50] Is this not the story of Australia after Whitlam, until Labor’s Hawke and Keating brought it to an end?

The story of Argentina’s economic malaise can be repeated, with a varied story line in many countries.

Argentina’s Economic Malaise – After Peron

Arturo Frondizi won the 1958 presidential election in a landslide. He failed to restore prosperity to the nation. He was replaced in another coup in 1966, which sought to restore national prosperity, beginning with more state control of money, wages and prices.

After 1966, in a radical departure from past policies, no doubt encouraged by the “smartest economic minds,” the Ministry of Economy announced a programme to reduce rising inflation while promoting competition, efficiency, and foreign investment. The anti-inflation programme focused on controlling nominal wages and salaries. It had striking benefits, with inflation decreasing sharply, decreasing from an annual rate of about 30% in 1965–67 to 7.6% in 1969. Unemployment remained low, but real wages fell, as they always will once Comparative Advantage theory is allowed to take control of economic thinking.

By 1970, the authorities were no longer capable of maintaining wage restraints, leading to a wage-price spiral. The lower real wages that are inevitable under the new economic orthodoxy are completely unacceptable to the majority of the people. In a democracy there can be only one outcome – an change of government.

Despair over the incompetent economic management of the post-Peronist period led to the election of the Peronist, Hector Cámpora in 1973 and then Perón himself soon after. When he died in 1974, he was succeeded by his wife, until she was deposed in a military coup in 1976.

The new Perónist regime was characterized by an expansive monetary policy, which resulted in an uncontrolled rise in the level of inflation. Here we have the same problems being repeated again – when will socialists ever learn?

Comparative Advantage – Continuing Problems

The dominance of the economic theory of Comparative Advantage led to a process of continuous decline. Just how the Argentinian economists thought that Argentina could compete with the USA with its own comparative advantages, which are numerous, is incomprehensible. Holding up manufacturing firms via state support just was not an effective band-aid solution. Argentina’s industrialization fell to levels maintained in the 1940. So much for a diversified economy, full employment, high wages, and political stability.

Argentina’s Economic Malaise – Today

The socialists were thrown out in 2015 and Mauricio Macri became president. At least Macri rejected socialist lies, but nothing would be fixed since he had swallowed economists’ Free Trade Lies. When he tried to implement the economists’ prescription to get Argentina back on its feet, he failed and Argentina’s Economic malaise continues today.

Yet economists still think that the solution to Argentina’s economic problems is more of the same, with the Financial Times completely perplexed that Macri’s presidency has not solved Argentina’s problems.

Argentina has embraced economic orthodoxy before, only to be blindsided by financial markets. This week’s mounting panic, which has seen the peso plummet and prompted the central bank to raise interest rates to 60 per cent, is just the latest example, prompting many to wonder: what has President Mauricio Macri got wrong?

The Financial Times cannot accept that the problem is in the economic model that it pushes every day of the week. Instead, it comes up with the lame excuse that one answer is “poor communication.” Actually, it is the only answer that it is willing to offer.

The same article cites an Argentinian economist, who says that there is no explanation for the current crisis.

“There is no logical explanation for what is happening,” said Christian Buteler, an Argentine economist, who called on the authorities to explain this “alarming” situation that is “completely out of control”.

The article concludes with argument from another Argentinian (capitalist) economist, reminiscent of arguments that I heard from (socialist) economists during the Whitlam era, “There is nothing to see here – all is OK.”

“[The problem is small] compared to the size of the market fear,” he says, arguing that the financing gap was small for Argentina’s $545bn economy.

Capitalist economists seem to think that ordinary workers in developed nations should accept ever falling wages and less secure employment. If challenged, they say that automation is the problem and will be increasingly the problem. Yet this is another lie. National states coped with the automation of industrial processes, but they will never be able to cope the with automation of other process if the real economic levels are handed over to global corporations in a fit of ideological blindness.