A carbon tariff will be required as a way of encouraging compliance in the event that COP26 arrives at a firm plan to cut real emissions to nearly zero by 2050 or 2060.

COP26 Glasgow

A consensus appears to be emerging that 2050 or 2060 should be set as the date when CO2 emissions should reach nearly zero, sometimes referred to as “net zero”.

Net zero, as a concept, is quite problematic. It envisages continuing to produce enormous amounts of CO2 and then burying it underground in what is described as “secure storage.” In addition, it also contemplates generating a large amount of electricity from biomass (possibly trees and thinnings) and burying this as well.

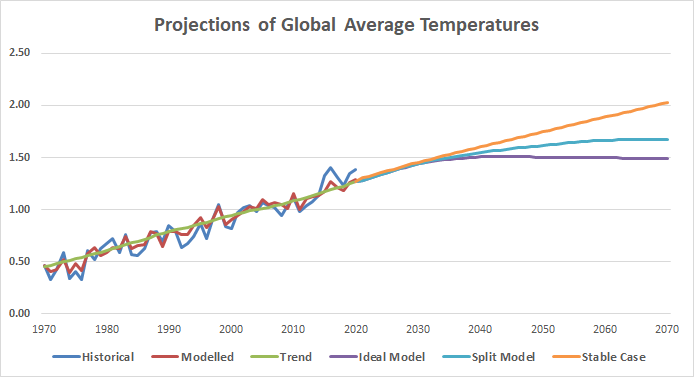

On the other hand, real zero is an unambiguous concept, but it is not necessary, at least in this century. This is because, even if natural gas and oil-based fuels are only cut by 90%, it is likely that global average temperatures will stabilise at the level when real CO2 emissions are cut to that level and all coal use is ended. Strategies to make cuts of this kind are discussed elsewhere. Some of these strategies are already being implemented: mostly they just need to be ramped up.

A target that could be agreed at COP21 is that all coal use be ended by 2060 and that the use of natural gas and oil-based fuels be cut to 10% of current levels by the same date. This is not the ideal case, which is targeting for 2050, but it may be the practical way forward.

Some nations may be willing to aim for 2050 as the end date instead of 2060, and this is to be encouraged. A 2050 end date could result in a rise in average global temperatures of 1.5C (the “Ideal Model”); an extension out to 2070 end date (only for non-OEDC nations) could result in average global temperatures of 1.7C (the “Split Model”); if emissions continue as at present it could result in average global temperatures of 2.0C (the “Stable Case”).

A carbon tariff is required

If COP26 is to be a success, there must be confidence in each nation that “other nations” will not exploit the system to enable them to gain a competitive advantage by continuing to use cheap, but CO2 intensive, fuels, like coal and natural gas. A carbon tariff could help to provide this level of confidence.

A carbon tariff could be applied to the exports from any nation that fails to meet the targets agreed at COP26. It would not require voluntary action by the defaulting nation, since the tariff will be automatically imposed by the importing nation that would impose the tariff in accordance with a new WTO rule. This rule would be agreed by the Glasgow conference and adding into the WTO rulebook.

When is a carbon tariff triggered

Let us say that the end date for “net zero” or nearly zero (whichever is agreed) is 2060 and the start date is 2020. Then let us assume that CO2 emissions will be reduced by equal increments until 2060. The carbon tariff would be triggered if the International Energy Agency deems that a nation’s CO2 emissions are not tracking down in line with the COP26 agreement.

For most nations, a fair way of calculating the target level for each year would be for the IEA to calculate per capita emissions. The USA’s per capita emissions could be starting point (plus a small contingency). The end point could be agreed at COP26 (such as zero for coal and 10% for natural gas and oil-based fuels). A straight line could be drawn between these two points and that would represent the target level for each year.

For some oil-producing nations this would not be fair (for example Qatar, with a small population and much oil and gas production). In this case, the target line could be drawn between the current level of CO2 emissions (plus an appropriate contingency) and the end point would be the level of emissions agreed at COP26. It also should be understood that emissions from small oil-producing nations actually depend on consumption in other nations.

The quantum of the carbon tariff

A carbon tariff of 20% is quite arbitrary, but it would serve the purpose of providing a very strong incentive to keep to the reductions agreed.

Some nations for whom a per capita target is appropriate are most at risk of breaching the target line in the early years. These are the USA, Australia and Canada. It is expected that each of those nations is already well motivated to cut its CO2 emissions.

Small oil producing nations are also a risk of breaching the target if the target is not set after taking their special situations into account.

All other nations are not likely to be faced with a carbon tariff until many years later. If the EU do not make any cuts it could come in 2040, but it is assumed that the EU will be aiming for 2050 target date and should have no difficulty in staying under the target line. The same should apply to all other nations.

The economic penalty of radically falling exports that would arise from a failure to avoid having a carbon tariff imposed by importing nations could be quite severe. If a carbon tariff is agreed, each nation would be well advised to act prudently in this matter.