Reserve Bank modelling indicated that, if there were global 20 per cent tariffs on EVERYTHING, the effect on Australia would be minimal. Clearly, tariffs are not a curse, or evil, or even a serious problem; and there are significant upsides to revisiting tariffs.

Reserve Bank of Australia

A recent freedom of information request resulted in the release of Reserve Bank modelling that concluded that, if there were a regime where every country slapped a 20 per cent tariff on every other country (global 20 per cent tariffs), the effect on the $A was not significant (it could appreciate or depreciate – implying it was a line ball). The effect on unemployment would be minimal – a 0.25% increase, and the effect on GDP would also be minimal – it would shrink by 1% by 2021.

This is not a proposition that is ever likely to been fairly considered by Australian Treasury, since it is ideologically committed to unrestrained free trade, as the relevant Australian government ministers make clear at every possible moment. However, it is a proposition that I presented for discussion in January 2018.

Consequences of Global 20 per cent Tariffs

While Reserve Bank modelling shows that global 20 per cent tariffs could be easily accommodated in Australia, such a change to the global tariff regime is also likely to have positive impacts on the body politic, which is the major interest of this blog. Two of these impacts are considered under the following headings:

- Reduced top-level income.

- Higher wages and more jobs.

Both of these movements in income will have the effect of reducing inequality across the Australian landscape. The question is whether this will be good for Australia as a whole. I would say “Yes,” but that is a personal and political judgment, not an economic one.

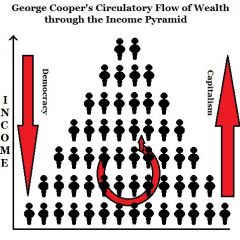

A regime recommending global 20 per cent tariffs would provide an economic model that aims to provide jobs for persons of every skill and education level, instead of the current model that leads to a winner-takes-all economy. Indeed, all western countries have a system in which some segments are able to compete very effectively, but with the rest of the population being left relatively worse off. This is source of current trend towards more inequality – it is not caused by a wicked capitalist plot. The source of this problem is the dominant economic theory, supported by major parties in most Western countries. (In Australia the strongest supporter of this economic theory was Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, a lifetime beneficiary of this approach. While it was not this Achilles Heel that brought him down, it did not help his cause, even though he was oblivious to this fact. The king is “dead;” long live the (new) king!)

Reducing Top-Level Income

Without being privy to the details behind the Reserve Bank modelling, one can be sure that the knock on GDP would primarily come from a decline in incomes of those who are currently winners in the current regime. These are globally competitive Australian firms, who would lose part of their first-mover-advantage. Since we do not have many of those, the impact would be relatively small. It would also impact on CEO salaries, since company boards would no longer have to select a CEO who can be the “best in the world,” in order to compete successfully with ever other CEO in the same industry. Competition would more likely to focus on finding a CEO who can compete within Australia. (Finding the “best CEO” is not always the best outcome, with Telstra’s and AGL’s unhappy experience being useful pointers in that regard.) This change would also have the socially desirable outcome of reducing inequality.

Higher Wages and more Jobs

Australia (and other Western nations obsessed with free trade) are currently following a view of an ideal world in which every country aims to do only those things that it is best equipped to do. Theoretically, a country does not grow its own food if someone is able to do it better; it does not make its own goods if someone else is able to make them cheaper; it even doesn’t educate its own people if they can get a better education elsewhere. It sells off all its businesses to the highest overseas bidder, ignoring the long-term consequences of this action.

Under this scenario, the government of each country allows the global market to have free play, based on the argument that, under this system, the collective entire global system is better off, in the (faint) hope that this will then trickle down to individuals in each and every country. At the same time, economists pay no attention to need for each nation to provide jobs for its own people, despite their respective education and skill levels. The world is considered to be a single pudding, with everyone having an equal chance to get their own piece (whether small or large).

The real world is not like this, thank God. In the real world most governments are responsible to their own people, not to some super-intelligent bureaucracy. (The EU is a notable exception, giving extraordinary powers to un-elected bureaucrats – a living lesson in the folly of delegating policy to a “super-intelligent” bureaucracy.)

The simple fact is providing jobs in a diversity of industries, businesses and government services provides better opportunities for everyone to get a job that suits his or her own talents. It is no good talking about Australia becoming a “knowledge economy” – not everyone has the talent to be a part of this new dreamland economy that “our betters” are planning for us.

While there is a place for a safety net, wages are best set as a function of the demand for workers, so that when there are more jobs than workers, wages will rise for those workers. Australians certainly do not want to repeat the situation in France where restaurateurs are short of workers and want to employ migrants who currently do not have legal rights to work, rather than attracting more entrants into their industry by increasing the wages of their own workers!

Any reasonable and competent government would work towards ensuring that a virtuous situation of jobs for all continues to lift the income of lower paid workers, through education, and improved skills at work.

Efficiency & Global 20 per cent Tariffs

There is a lot of nonsense spoken about the improvement of efficiency as a result of removing tariffs from Australian manufacturing. The plan fact is that the combination of tariff cuts and the currency revaluation were so severe they led to the smashing of Australian manufacturing. The car industry is a case in point. The EU have a 15 per cent tariff regime for cars; Australian leaders thought that a 5 per cent tariff was so good it reeked of “economic virtue.” Yet the EU still has a car industry, despite competition from Asia. Add to this the failure to effectively manage the $A during a period of over-valuation of the $A against the $US, which meant an effective 40% negative tariff working against Australian manufacturing. We congratulated ourselves on our economic management while “Rome burned!”

Innovation

Australia’s political leaders hope that “innovation” will be Australia’s economic saviour in the coming uncertain times. Having smashed manufacturing in a search for impossible to achieve domestic efficiency – sufficient to overcome cheaper labour overseas and larger domestic markets – these leaders need to find something new.

There is some hope of this front. Australia’s mining industry is a world leader, and has generated sufficient profits to be able to fund continuous innovation. Australia’s innovation potential has delivered three world-competitive health product and service companies – CSL, Cochlear and ResMed. It has also delivered four world-class players in Information Technology.

In this way, we can see innovation has delivered good returns for those who are able to be central players in these fields. The profits generated mean that further innovations are able to investigated and pursued if they look promising. The same profits are also able to fund above average salaries.

Yet innovation of this kind is of little direct assistance to those who are not in the top 10% of ability and advantage. It is too easy for the government to just sit back and admire the success of those firms and sectors. The real challenge for the nation’s government is to aid the remaining 90% to achieve success appropriate to their own natural abilities.

Given the natural creativeness of Australians, and their aspirations for a “better” life, all the Australian government has to do is ensure that Australian firms can earn sufficient profit to fund their own innovation programmes. Yet it cannot do this by crushing employee wages and thereby helping firms to increase their own profits by that route. It must somehow increase the potential for higher margins between revenue and costs.

Insofar as governments have any role in this, the first step is to decide whether it wants to establish conditions that serve primarily to increase efficiency of firms – by making all businesses compete on a “level playing field” with the rest of the world – or by providing local firms with a small advantage over global competitors.

Australia had tried the “efficiency route” and delivered a very unpleasant smelling result. It is about time it tried the “innovation route” and then to see what this will deliver.

Global 20 per cent Tariffs & a Level Playing Field

There is no such thing as a “level playing field.” Each country is different, and the pursuit of a level playing field will just mean progressively lower wages for everyone except the most successful of our fellows. This is because of the current world surplus of labour; this means global capital can always seek out the lowest wage employee that can do the job that it wants to have done. Ironically, this is the course of action required by governance conventions – boards have little choice in this matter.

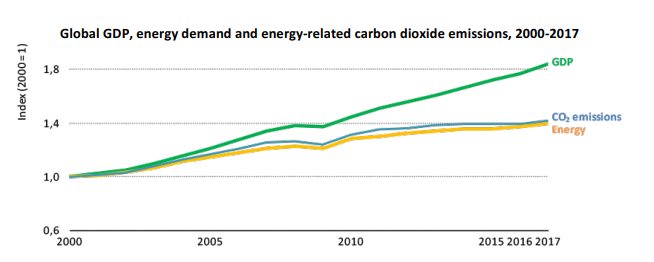

The current WTO objective of “lifting all boats” by lowering all tariffs to zero rating is entirely misconceived. Rather, this strategy will trap developing nations in a permanent dependency on the West. It is something that China will never countenance, nor should any nation, whether developed or developing.

A regime with a target of global 20 per cent tariffs would give emerging industries in developing and developed countries a chance to find a modest level of support so that they can find their feet. It never needs to be reduced below 20 per cent, unless there really is a compelling case for goods to be 20 per cent cheaper. What would be the argument for that? The wealthy getting luxury goods cheaper?

Conclusion

It is cringe-worthy for economists to cite 1930s protectionism as if it provided the evidence for embracing free trade. Don’t they know that the 1930s were a very difficult period because of the crash of the world economies from over-active speculative activities in the 1920s? A similar thing happened in 2007 and 2008, and the worldwide rejection of protectionism did little to make recovery faster than in the 1930s. Food for thought, eh?

Don’t economists know that America’s economic powerhouse was established in the 19th century, building its strength behind tariff walls? Don’t they know that the world became a much more prosperous place at the same time as protectionist regimes were in place in most of the nations of the world, namely, in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s?

Rather than protectionism being ridiculous, as opponents of Donald Trump seem to think, the arguments presented here are just standard economic principles. Unfortunately, free trade advocates have stopped thinking from first principles, and have adopted a convenient, if bogus, theory.

If economists did a bit more original research, as well as looking at history, they would realise that an approach that led to global 20 per cent tariffs would benefit all nations, and certainly “lift the boats” of all developing nations. All that is required is for national economic leaders to seize the moment and the opportunity and argue the case cogently.