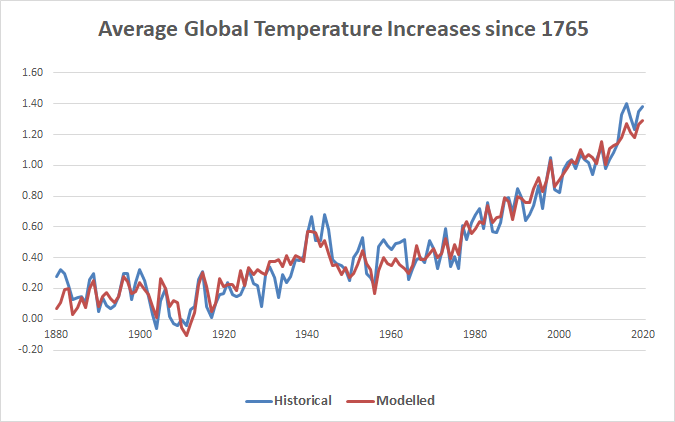

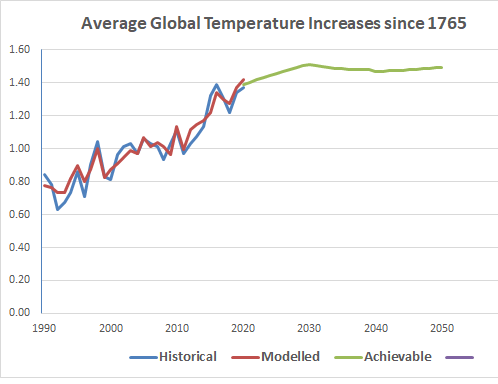

Will COP 26 be an echo chamber of plausible responses to the climate crisis or a forum that drives change? Will COP 26 be the moment that stops the increase in global temperature, or will it be drowned in politics?

Methane at COP 26

Since 1950 atmospheric methane (CH4) has grown from 1220 ppb to 1870 ppb. On its own, it has increased temperature during that period by 0.13C. Breaking up this increase by its components reveals the following:

- 57% from fugitive emissions from natural gas.

- 25% from ruminant animals (both farmed and wild).

- 13% from waste.

- 9% from fugitive emissions from coal.

- 6% from rice cultivation.

- 6% from biomass.

Most of attention in regard to methane emissions has been given to belching from ruminant animals. Yet cutting red meat (and rice) from our diet is not a matter for COP 26, IMO. Yet there are other matters to be considered at this conference. For example, what about fugitive emissions from natural gas?

Let us suppose that in the next 10 years we were able to cut methane emissions from everything except ruminant animals and rice cultivation by 50%. In this case the atmospheric methane would fall from 1870 ppb to 1730 ppb. This would be just the beginning, for it would continue to fall out to 2100. In other words, instead of contributing to the growth in global average temperature, it would mitigate the increases from other sources.

The move from coal to natural gas for electricity generation may have been a good idea at the time, but we should not now chose to use these gases for electricity production. If this is done and also we cut methane emissions from waste as well as changing from biomass to electrical cooking and heating, this would reduce atmospheric methane, without doing anything else. So a cut in methane emissions by 2030 should be on the COP 26 agenda.

F-Gases at COP 26

When the Montreal Protocol was established in 1990, it was realised that moving from ozone-depleting CHCs to other gases would increase atmospheric greenhouse gases. At the time it was agreed that certain gases mentioned in the Montreal Protocol gases would be fazed out from 2025. Yet there is no sense that this commitment is being taken seriously in the run-up to COP 26. It should be included in the final agreement.

Electricity Production: Low CO2

Presently, there are only two viable models for electricity production in a low CO2 environment: nuclear and intermittent sources. While nuclear is favoured in some places. It is not favoured in other places. In any event, it would appear that following this route is very expensive. On the other hand, intermittent sources, by their very nature, are unreliable.

It is true that cyclic fluctuations through the week can be managed through an appropriate level of storage, which could be via pumped-hydro, batteries and other more experimental means of storing electricity. Therefore, it is not cyclic and predictable fluctuation in demand that is preventing the take up of intermittent power supply. The problem is in the unpredictable nature of supply. The thing that is holding back more widespread use of intermittent supply of electricity is the lack of a plan to cover the shortfall in electricity supply when the wind or the sun fail to deliver the quantum of electricity that is required. This is the biggest problem in moving to a more complete dependence upon intermittent / renewable supply of electricity.

For nations that are already industrialised there is a simple solution at hand, even though it cuts across the ideological resistance to coal. Yes, the solution is to use coal-fired generators (and any existing redundant gas-fired generators) to provide back up generating capacity in the case of a failure in supply of electricity from renewable sources. In the short-term, the existing coal and gas-fired generators could be brought on line in the event of a failure of supply. Even with the current configuration, this should happen in less than 20% of the time once the intermittent supply system generally provides 100% of electricity power. This approach will ensure a 80% cut in the CO2 emissions from this source. On the other hand, it does mean that banning coal from the electricity-generation field will not be possible, or even practical (if one really wants to cut CO2 emissions).

In a system that does not use nuclear power, it would appear that a properly designed system will provide all power to consumers from renewables and from storage. Under this system, the storage would be replenished from time to time using coal-fired generators. This would only happen when the storage falls below a level in which the operators believe is too low for a measured guaranteed security of supply. Under this scenario, the coal-fired generators would run flat-out until the storage was replenished.

In a system that uses nuclear power, the power stations could run continuously, replenishing the storage in a balanced manner.

Oil-based fuel

We already know how to cut the usage of oil-based fuels for passenger vehicles and light trucks. The simple solution is for each country to mandate that new vehicles must be fully electric. However, this will bring many problems in its wake. These include a complete replacement of the refueling system and potential massive increases in the prices of raw materials. It would be more sensible to move more slowly.

The ideal solution, hopefully to be discussed at COP 26 is for each nation to move towards mandating hybrid, plug-in hybrids and fully electric vehicles for new vehicles well before 2030. The market can then manage the extra cost for each type of vehicle. Since a simple hybrid is not much more costly than a vehicle with a 100% internal combustion engine, this can be the starting default. Even this will cut the consumption of petrol by about 30-40%, which will lead to a significant reduction in CO2 emissions from this type of vehicle.

Solutions for heavier trucks and buses and ships can be considered at a later period. The end result should be that by 2030 we will have a solution prepared for all oil-based fuels.

Cement and Steel

Solutions are currently being considered for the CO2 generated in these two processes. Time is required to allow feasible and proven solutions to emerge.

Conclusion

Significantly cutting greenhouse gas emissions in this way by 2030, in the areas where we already know how to do it, will avert the climate change crisis, and put us on a path to prevent global warming since industrialisation of more than 1.5C. Early and radical action is required.

Such action should be legacy of COP 26. The question remains, will the representatives have the courage to take the actions that are required? Will the members present be willing to abandon those ambitions that will not lead to that outcome, but will hinder this desirable result.